Technology to measure the flow of subatomic particles known as antineutrinos from nuclear reactors could allow continuous remote monitoring designed to detect fueling changes that might indicate the diversion of nuclear materials. The monitoring could be done from outside the reactor vessel, and the technology may be sensitive enough to detect substitution of a single fuel assembly.

The technique, which could be used with existing pressurized water reactors as well as future designs expected to require less frequent refueling, could supplement other monitoring techniques, including the presence of human inspectors. The potential utility of the above-ground antineutrino monitoring technique for current and future reactors was confirmed through extensive simulations done by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“Antineutrino detectors offer a solution for continuous, real-time verification of what is going on within a nuclear reactor without actually having to be in the reactor core,” said Anna Erickson, associate professor in Georgia Tech’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering. “You cannot shield antineutrinos, so if the state running a reactor decides to use it for nefarious purposes, they can’t prevent us from seeing that there was a change in reactor operations.”

The research, reported August 6 in the journal Nature Communications, was partially supported by a grant from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). The research evaluated two types of reactors, and antineutrino detection technology based on a PROSPECT detector currently deployed at Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR).

Antineutrinos are elementary subatomic particles with an infinitesimally small mass and no electrical charge. They are capable of passing through shielding around a nuclear reactor core, where they are produced as part of the nuclear fission process. The flux of antineutrinos produced in a nuclear reactor depends on the type of fission materials and the power level at which the reactor is operated.

“Traditional nuclear reactors slowly build up plutonium 239 in their cores as a consequence of uranium 238 absorption of neutrons, shifting the fission reaction from uranium 235 to plutonium 239 during the fuel cycle. We can see that in the signature of antineutrino emission changes over time,” Erickson said. “If the fuel is changed by a rogue nation attempting to divert plutonium for weapons by replacing fuel assemblies, we should be able to see that with a detector capable of measuring even small changes in the signatures.”

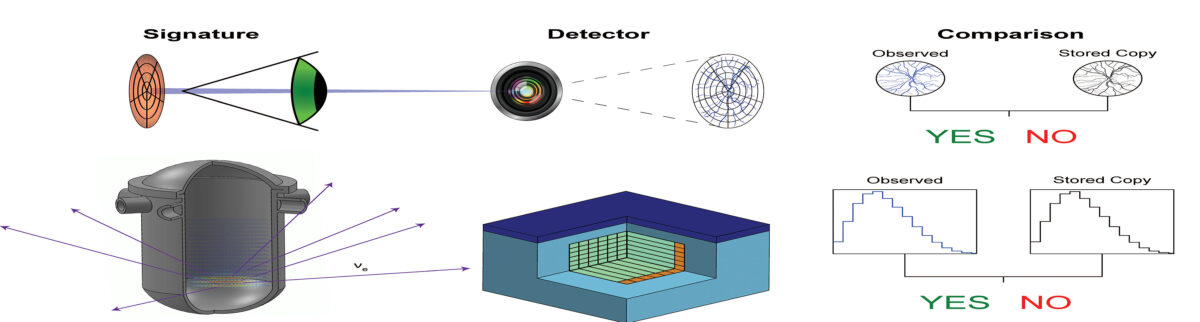

The antineutrino signature of the fuel can be as unique as a retinal scan, and how the signature changes over time can be predicted using simulations, she said. “We could then verify that what we see with the antineutrino detector matches what we would expect to see.”

In the research, Erickson and recent Ph.D. graduates Christopher Stewart and Abdalla Abou-Jaoude used high-fidelity computer simulations to assess the capabilities of near-field antineutrino detectors that would be located near – but not inside – reactor containment vessels. Among the challenges is distinguishing between particles generated by fission and those from natural background.

“We would measure the energy, position and timing to determine whether a detection was an antineutrino from the reactor or something else,” she said. “Antineutrinos are difficult to detect and we cannot do that directly. These particles have a very small chance of interacting with a hydrogen nucleus, so we rely on those protons to convert the antineutrinos into positrons and neutrons.”

Nuclear reactors now used for power generation must be refueled on a regular basis, and that operation provides an opportunity for human inspection, but future generations of nuclear reactors may operate for as long as 30 years without refueling. The simulation showed that sodium-cooled reactors could also be monitored using antineutrino detectors, though their signatures will be different from those of the current generation of pressurized water reactors.

Among the challenges ahead is reducing the size of the antineutrino detectors to make them portable enough to fit into a vehicle that could be driven past a nuclear reactor. Researchers also want to improve the directionality of the detectors to keep them focused on emissions from the reactor core to boost their ability to detect even small changes.

The detection principle is similar in concept to that of retinal scans used for identity verification. In retinal scans, an infrared beam traverses a person’s retina and the blood vessels, which are distinguishable by their higher light absorption relative to other tissue. This mapping information is then extracted and compared to a retinal scan taken earlier and stored in a database. If the two match, the person’s identity can be verified.

Similarly, a nuclear reactor continuously emits antineutrinos that vary in flux and spectrum with the particular fuel isotopes undergoing fission. Some antineutrinos interact in a nearby detector via inverse beta decay. The signal measured by that detector is compared to a reference copy stored in a database for the relevant reactor, initial fuel and burnup; a signal that sufficiently matches the reference copy would indicate that the core inventory has not been covertly altered. However, if the antineutrino flux of a perturbed reactor is sufficiently different from what would be expected, that could indicate that a diversion has taken place.

This figure shows the principle of reactor operation verification with antineutrino monitors. The process for verifying reactor inventory integrity with antineutrinos bears similarities to biometric scans such as retinal identity verification.

The emission rates of antineutrino particles at different energies vary with operating lifetime as reactors shift from burning uranium to plutonium. The signal from a pressurized water reactor consists of a repeated 18-month operating cycle with a three-month refueling interval, while signal from an ultra-long cycle fast reactor (UCFR) would represent continuous operation, excluding maintenance interruptions.

Preventing the proliferation of special nuclear materials suitable for weapons is a long-term concern of researchers from many different agencies and organizations, Erickson said.

“It goes all the way from mining of nuclear material to disposition of nuclear material, and at every step of that process, we have to be concerned about who’s handling it and whether it might get into the wrong hands,” she explained. “The picture is more complicated because we don’t want to prevent the use of nuclear materials for power generation because nuclear is a big contributor to non-carbon energy.”

The paper shows the feasibility of the technique and should encourage the continued development of detector technologies, Erickson said.

“One of the highlights of the research is a detailed analysis of assembly-level diversion that is critical to our understanding of the limitations on antineutrino detectors and the potential implications for policy that could be implemented,” she said. “I think the paper will encourage people to look into future systems in more detail.”

CITATION: Christopher Stewart, Abdalla Abou-Jaoude and Anna Erickson, “Employing antineutrino detectors to safeguard future nuclear reactors from diversions,” (Nature Communication, 2019). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11434-z

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu).

Writer: John Toon